On your (automotive) (trade)marks, get set, go!

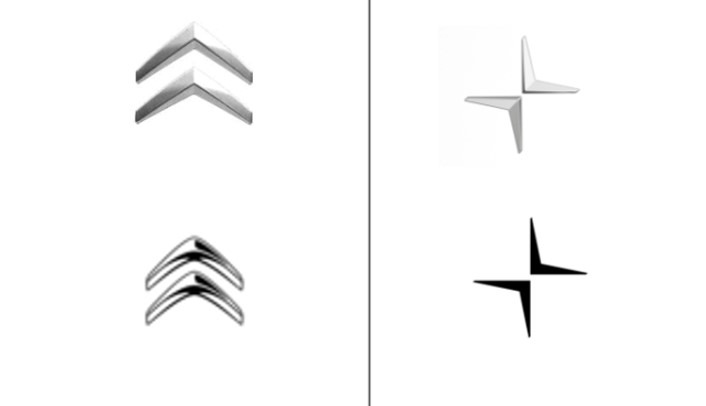

Citroën can count on its chevrons, protected as a figurative trademark and confirmed as having a distinctive character by the Paris Court of Appeals in late 2021 and the EUIPO in April 2022, to block new competitor Polestar. Based in Sweden and car preparer for Volvo company, Polestar was unable to enter the French market of car manufacturers.

Insights on a two-stage legal battle and the distinctive signs that car manufacturers can use to protect their position and the related investments.

The press and various internet forums had denounced the visual connection between the Polestar logo and that of Citroën in eloquent terms: “the sketch of the North Star which resembles, by an unfortunate chance, the old chevrons of Citroën that some joker would have separated and turned over” (Challenges) or “the Jerks! (sic) they recycled the Citroën chevron” (Autoplus website forum).

The first part of the legal battle between the parties took place before the Paris Judicial Court and then before the Paris Court of Appeals which issued on December 14, 2021 a decision that upheld the first instance judgment.

The weak overall resemblance between the signs in question had led the judges to dismiss the alleged infringement, the Court of Appeals having in this matter confirmed the reversal of the case law of the Court de Cassation (French Supreme Court) which considers that the application for registration of a sign as a trademark does not constitute an act of infringement.

However, in the case at hand, this was not an isolated trademark application, as Polestar had widely announced its plans to market cars online from the Polestar.com website, during 2020, as well as the development of a network of dealerships, the financing of which was then under negotiation.

It is in any case on the question of the infringement of the trademark with a reputation that Citroën was able to successfully defend itself:

“Given the exceptional reputation of the Citroën double chevron trademarks at issue and their strong distinctiveness acquired through intensive use supported by extremely significant advertising investments, and the fact that the conflicting signs are used to designate the same products, namely motor vehicles, the use by the Polestar companies of the contentious signs leads to an infringement of the distinctive character by dilution and blurring of said trademarks exploited in the automotive industry where the number of manufacturers is relatively limited”.

As for the products concerned and, therefore, the relevant public, although Polestar had argued that the market segment was different, the Paris Court of Appeals took into account the fact that Citroën markets hybrid vehicles and was to enter the new market of electric cars.

As for the signs in question, the judges compared them according to the established method, only a visual and conceptual apprehension being relevant in the case at hand.

And in line with Community case law[1], the Paris Court of Appeals considered that even in the presence of a weak similarity between the signs – and thus without any resulting risk of confusion, the relevant public nevertheless made a connection between the trademarks in question.

To rule so, the judges based their assessment on several factors, including a high level of reputation of the earlier trademark, qualified as “exceptionally high” and “strongly increased by the intensive use that has been made of it so that the distinctive character of the earlier marks is high”.

In practice, three types of infringement of a trademark with a reputation can be sanctioned according to the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union, i.e., detriment to the distinctive character of the earlier trademark, detriment to the repute of that trademark and, lastly, unfair advantage taken of the distinctive character or the repute of that trademark[2].

In the case at hand, detriment to the repute of the Citroën logo was established, and the Paris Court of Appeals found that the distinctive character of the trademark was damaged by “dilution and blurring”.

The second part of the legal battle took place before the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) as Polestar brought an action seeking the cancellation of the contentious figurative trademark. This bold and risky step did not have the expected effect and, on the contrary, rather reinforced the distinctive character of the sign.

In a rather brief decision, the EUIPO first recalled its legal independence from national and European courts, including the Paris Court of Appeals (in the above-mentioned decision). It then ruled that Citroën’s chevrons were intrinsically distinctive without it being necessary to rule on the acquisition of distinctiveness through use.

Regarding the relevant public, the EUIPO held that is consisted both of the average consumer, who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, and of more highly attentive consumers for some services covered by the Citroën trademark application, in particular Class 36 financial services.

Polestar had argued that the design of the contentious logo was basis, but the EUIPO held that a specific design is a sufficient condition, without the need to justify distinctiveness through Citroën’s use of the sign or the heavy investments related to it, as the Paris Court of Appeals had done in its decision.

While the trademark has not been invalidated, Polestar’s conviction and, above all, the ban on the use of its logo in France remain in force. As it stands, when visiting the Polestar website from France, web surfers can read the following message “Access to the Polestar site is not accessible to the French public due to territorial restrictions on the use of French trademarks n°016898173 and n°01689532”.[3] But for how long? What will happen at the end of the six-month period for which said ban was ordered?

In any case, these decisions somewhat reinforce the protection of car manufacturers’ signs, beyond the umbrella brands that are their names.

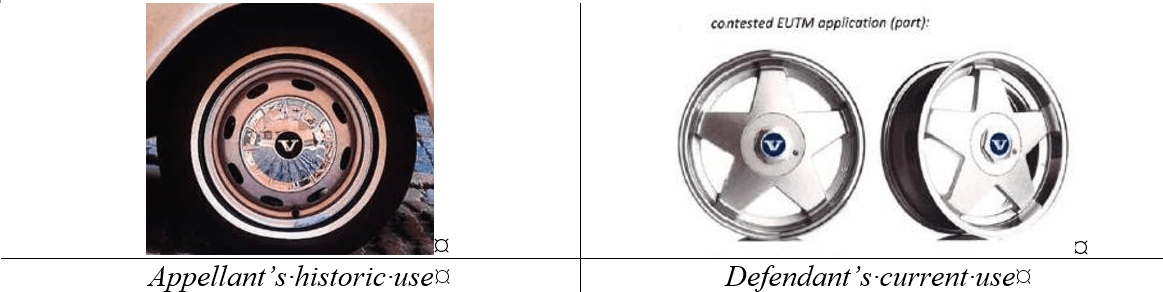

The judges even have an extensive view of the protection of automobile logos. This is how Volvo was able to oppose the use of the “V” letter in its trademark[4].

The EUIPO indeed considered that given the use of a nearly identical font for this letter (which was the dominant element of the contested competing trademark), the use of the same colors in the conflicting signs, and the same circular structure, “the relevant public will certainly establish a link between the conflicting signs, especially when taking into consideration the high reputation of the earlier trademark and the fact that the conflicting goods are also identical”.

It further clarified this concept of link as follows:

“There is sufficient resonance triggered between the signs in conflict, such that the leitmotifs conveyed by the earlier rights to consumers will, at least, cause them to be more favourably disposed to purchase the products of the defendant. In other words, there is a risk of free-riding whereby the image of the earlier rights which enjoy immense reputation and which project values such as safety, reliability and quality will be transferred to the goods covered by the mark applied for, with the result that the marketing of those goods will be made easier by that association with the earlier marks with reputation.”

And beyond the logo, car manufacturers also protect as a trademark the models of the vehicles they market, whether it is a name or a number.

In this respect, Porsche had been in conflict with Peugeot in the 1960’s concerning the name given to the successor of the 356. Peugeot reportedly vetoed the prototype of the 901 model to the benefit of 911 model, related to the fact that the firm had reportedly registered since 1929 – and the launch of its 201 model– all the numbers taking back a central 0.

Regarding car names, car manufacturers have a great deal of freedom, including the use of birth names, such as “Megane”, “Clio” or “Logan”. It should be recalled that, at the time the “Zoé” model was launched, Renault won the lawsuit that had been initiated by parents whose family name was Renault, whose daughter’s first name was “Zoé” and who wished to prevent their daughter from being the subject of mockery, but in vain[5].

And to go one step further, car manufacturers can protect not only the name of their vehicles, their aspect (by copyright, designs and models), any technical innovation which they contain pursuant to the patent, but also the layout and the contents of their websites by copyright and the associated domain names, and so on… Indeed, communication also includes slogans which can be registered as trademarks (like “Das Auto” for Volkswagen), including in a sound or multimedia form (Renault has already done it and Hyundai also for a jingle). Finally, they can also protect their physical sales outlets, through copyright or figurative trademark.

Car manufacturers have, therefore, a wide range of rights to protect themselves from new competitors, whether intellectual or industrial property rights or the possibility to rely on ordinary law that regulates unfair competition or free riding. In this respect, it should be noted that the damage to the repute of the earlier trademark is in fact very similar to free riding as it uses the same mechanism (taking undue advantage of the repute of the competitor or third-party operator by following in his footsteps without paying or sharing any costs).

[1] CJEU, November 27, 2008, Intel (C-252/07)

[2] As demonstrated by the EUIPO in the Volvo/V-Wheels decision dated March 3, 2021 (R0776/2018-4)

[3] https://www.polestar.com/fr-be/

[4] EUIPO, Volvo/V-Wheels decision dated March 3, 2021 (R0776/2018-4)

[5] Paris First Instance Court, Summary Division, November 10, 2010, No. 10/59262

Strategic Lawyering

Strategic Lawyering